A caveat: Our thoughts here are not to be interpreted as a blanket approval for free trade agreements (FTAs) in all their different forms. Trade agreements — whether regional or global — do impact human rights adversely, and we need to approach them with caution. Each agreement must be critically scrutinised on a clause-by-clause basis.

Trade liberalisation can have positive and negative impacts on the environment. The growth of economies and their expansion will inevitably increase pollution and degrade natural resources. Also, although outside the scope of this topic, the controversial investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) clause in trade agreements is worth noting.

Recently, Canadian company TC Energy Corporation (TCEC) filed an ISDS claim for more than USD15 billion against the United States government because the latter cancelled the Keystone XL oil pipeline project due to environmental concerns. TCEC is alleging that the government violated the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

The ISDS mechanism poses a chilling effect on environmental regulation as it may act to deter states from enforcing human rights obligations, especially when they come into conflict with business interests with safeguards embedded within FTAs.

Notwithstanding the weaknesses of FTAs, which must not be overlooked, there are also benefits that trade agreements can bring to the table regarding environmental protection. Through trade agreements, more incentives and opportunities can be made available to support the capacity of local companies in improving their management of environmental impacts. Trade and investment in “green” goods and services that enhance environmental performance will only increase as parties seek to remove potential tariff and non-tariff barriers imposed on them.

Further, we make the following four points.

Increasing uptake of environmental concerns

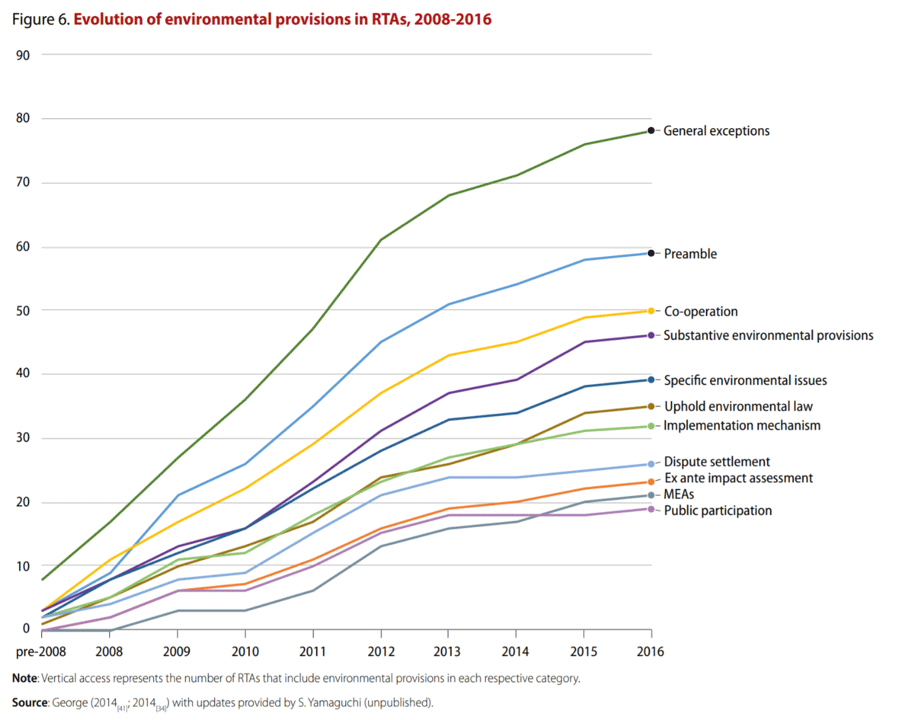

First, we have seen an upward trend in the use of environmental provisions in trade agreements. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) tracked the typology of these provisions from pre-2008 to 2016 and found a marked increase in the number of trade agreements that included such provisions.

For example, clauses on substantive environmental issues were found in 45 regional trade agreements (RTAs) in 2016, an increase from less than ten before 2008. The diagram below, reproduced from the report, OECD Work on Trade and The Environment: A Retrospective, 2008-2020 (2021, p. 32), illustrates this point.

Why? These clauses were inserted to ensure that trade liberalisation does not damage but instead positively contributes to environmental protection. They indicate an increasing awareness and acceptance by governments and corporations of their environmental responsibility.

Driving legal and structural change

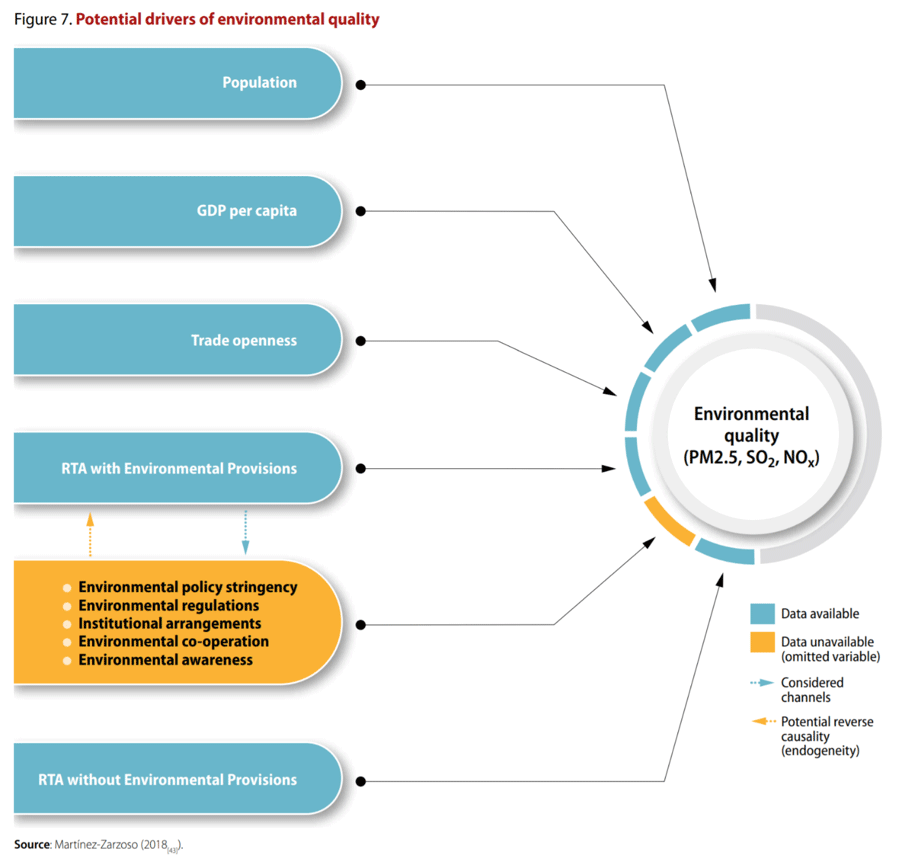

Our second point is that environmental provisions in trade agreements act as crucial drivers for governments and companies to implement better environmental regulation and institutional frameworks. Commitments in trade agreements serve to enhance the policy coherence between environmental and trade targets.

Whether these structural enhancements translate to actual environmental protection domestically is, however, inconclusive. Numerous political and social factors are at play when considering why protection is still deficient despite improved legal and regulatory architecture.

Nevertheless, there are positive signs. Martínez-Zarzoso’s empirical study in 2018 found that there is “a statistically significant relationship between RTA membership, with or without environmental provisions, and improved environmental quality for two out of three of the pollutants investigated” (see diagram below and OECD Work on Trade and The Environment, p. 34), namely, sulphur dioxide (SO₂) and nitrogen oxide (NOx). For SO₂ and NOx, the magnitude of the effect is slightly larger for agreements with environmental provisions than for those without. Further research is necessary to substantiate or falsify this link.

While actual environmental impacts may be difficult to quantify, trade agreements with environmental provisions provide a unique opportunity for governments to update their laws, practices, and policies to meet global standards — if there is the political will to do so.

Malaysia is due to ratify the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). The CPTPP strives to promote, among others, sustainable development, corporate social responsibility, and environmental protection and conservation.

Chapter 20 of the CPTPP on the environment commits States Parties to pursue high levels of environmental protection, enforce environmental laws effectively (including to ensure that allegations of environmental law violations are investigated, and transparent judicial enforcement mechanisms and sanctions are available domestically), and promote transparency, accountability, and public participation through consultations regarding environmental matters.

While Malaysia arguably meets the basic standards expected, legal and implementation gaps are still in evidence; business activities and local communities often come into conflict. Malaysia’s proposed National Action Plan (NAP) on Business and Human Rights, with a focus on labour, governance, and the environment, will hopefully further cement the link between the environment and human rights in the country. The NAP and the CPTPP ought to work hand in glove to heighten the protection of and respect for our environmental rights.

Unfortunately, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which Malaysia signed and is expected to ratify by the end of 2021 or latest by the first quarter of 2022, does not expressly emphasise nor advance environmental cooperation and protection. It has no provisions on labour standards nor transitions to greener industries. It has been described as a “squandered opportunity” for international trade to advance human rights and environmental protection.

Impacting the way Malaysian companies do business

At a more micro level, how do international trade agreements impact businesses on the ground? Much depends on how the Malaysian government implements its obligations under the agreements. This is our third point.

We highlight three clauses from the CPTPP to illustrate our argument. Two provisions are mandatory, while one is voluntary:

- Articles 20.8 and 20.9 provide for broader participation and scrutiny by the Malaysian public regarding the government’s implementation of Chapter 20. The government is obliged to establish a mechanism to respond to requests for information and written submissions filed by the public. If a submission asserts that the government is failing to enforce its environmental laws effectively, other countries may request that a Committee on Environment (established under the CPTPP) discuss the submission.

- Under Article 20.5, the government must take measures to control the production and consumption of, and trade in, substances that can deplete or modify the ozone layer in a manner that results in adverse effects on health and the environment.

- Article 20.15 states that transition to a low emissions economy depends on domestic circumstances and capabilities. This provision is couched in voluntary terms. Parties are to cooperate on matters such as energy efficiency, clean and renewable energy sources, emissions monitoring, and addressing deforestation and forest degradation. A cooperation framework is spelt out but does not impose a binding duty on the government to meet any required targets.

We assert that the public participation mechanism in Articles 20.8 and 20.9 will change the landscape of environmental rights advocacy in Malaysia. Significant public pressure through the submission process will ensure greater accountability from the government to curb business operations that are detrimental to the environment. In turn, logic dictates that stringent governmental controls will compel businesses to stop harmful practices.

In relation to Article 20.5, Malaysia in October 2020 ratified the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer 1987 to phase down hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs). The target is to reduce the production and consumption of HFCs by 80% by the year 2045, based on a calculated baseline. New regulatory measures to prohibit or control business practices and substances that emit HFCs will have to be implemented to achieve the Kigali target and in turn, comply with Article 20.5.

In terms of the non-binding Article 20.15, the question is: To what extent will the Malaysian government engage and collaborate with other governments to accelerate the country’s transition to a low emissions economy? Malaysia should embrace the opportunity to build capacity among its line agencies, civil society organisations, and businesses to progress collectively on the agenda. Because there are no quantifiable indicators set out under 20.15, it will not be easy to assess the provision’s impact on companies. However, this should not relieve businesses from working towards a low-carbon transition in their environmental goals, in line with global trends.

In short, the environmental provisions will impact business operations if the government adheres to its international commitments, tightens its regulations, and imposes more stringent requirements on companies to manage their environmental risks.

Staying ahead of the curve

On to our final point. What are some steps that Malaysian companies can take to become forerunners in protecting the environment and consequently, the human right to a clean and healthy environment? How can they align their practices with international standards?

Internally, there is an urgent need to take a longer view of climate risks. Digitalisation revolutionalised business, so too will climate change. Business priorities have to be revamped — not only to comply with legal obligations, but also to uncover environmental impacts that need to be mitigated, and to recognise that environmental rights are also human rights.

Further, the precautionary principle first mooted in 1992 in the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development should be embedded into every stage of an organisation’s operations. Action to prevent or avert serious harm to the environment should be taken now and immediately. Delaying action until there is compelling evidence of harm will prove costly, both to avert the harm and to repair the business’ damaged reputation.

In summary, three key steps are suggested:

1. Evaluate your business’ human rights and environmental risks and opportunities

Common concerns include deforestation, pollution, emissions, waste management, and the use of natural resources such as water, raw materials, and energy. A human rights due diligence exercise should be conducted to assess the impact of your operations on the environment and the communities affected, and to take action to prevent or mitigate them. Your value chain should be mapped and assessed as well.

Where possible, scenario modelling should be done to examine possible future events and to predict their possible outcomes – the “what if?” assessment. The modelling will further clarify the organisation’s risks and opportunities.

2. Develop, adopt, and implement your environmental strategy consistent with human rights standards

Post-assessment, set specific and measurable targets as part of your business objectives and environmental strategy. Depending on the nature of the business, it may include embracing decarbonisation as a business opportunity and incorporating carbon removal into your supply chains and operations. The implications of these strategies on humans should be expressly identified.

Genuine and effective consultative processes must also form a core component of all human rights-based strategies, be it with employees or “sensitive receptors” such as nearby residents or indigenous groups whose lives are impacted by business activities.

3. Monitor, evaluate, and report your gains and losses transparently

Investors and consumers are keen to understand how the organisation reviews and evaluates its human rights compliance and performance. Often-used methods include sustainability self-reporting or disclosures that incorporate human rights indices to rate and benchmark companies’ performances.

The goal must be to regularly communicate the results of the measures taken, supported by truthful and relevant information for public consumption.

This article is adapted from remarks delivered by Edmund on 24 September 2021 at a webinar on The Role of Free Trade Agreements in Promoting Sustainable Business and Human Rights: Fostering Responsible Trade Practices, Sustainable Supply Chains, and Human Rights Compliance, organised by the Business Council for Sustainable Development (BCSD) Malaysia in partnership with the Raoul Wallenberg Institute of Human Rights and Humanitarian Law (RWI). Edmund contributed to a panel discussion on the implications of free trade agreements on human rights and the environment.