Over the years, the Bar Council has successfully advocated for improvements to our criminal justice system. I recall vividly, for instance, the strong representations that were made before the Royal Commission into the Malaysian police force, resulting in the Commission’s recommendations to amend sections 113 (removing the power to take caution statements) and 117 (shortening remand periods) of the Criminal Procedure Code (CPC). Both recommendations were made to reduce police abuse and inducement to have a suspect confess to his or her crime.

But more needs to be done.

Long-standing issues faced by criminal defence lawyers are documented here. The Bar Council must act.

- Inequality of arms at trial

The prosecution still does not disclose witness statements and unused material, even if they could clear the accused from guilt and support the defence case. In drug cases, the underlying documents to the chemist’s report (such as the working papers of the tests done) are not provided for the defence to scrutinise the evidence thoroughly. The current disclosure rules under section 51A of the CPC are insufficient to meet fair trial standards. Non-compliance with 51A attracts no sanctions against the prosecution. Therefore, trial by “ambush” by the prosecution is a daily practice in the Malaysian courts. - Lack of immediate legal representation during pre-trial stages

While it is often said that everyone has a right to legal counsel, it is not respected in practice. Specifically, when one is arrested or remanded, it is often done either without the knowledge of the detainee’s family or the opportunity for a lawyer to be engaged. The police will nevertheless proceed with questioning without the presence of counsel. This heightens the risk of illegally obtained evidence, such as the making of involuntary statements by the suspect. - Application of assumptive legal presumptions in drug and corruption cases

Legal and factual presumptions have been written into our laws to make it easier for the prosecution to secure convictions. For example, in drug cases, there are presumptions relating to possession and trafficking, and in corruption offences, there are presumptions of corrupt gratification. The government justifies them by saying that it is extremely difficult for the prosecution to prove these elements by the usual rules of evidence. While the presumptions are rebuttable, the absence of other fair trial safeguards (some of them mentioned above) makes it almost impossible for the accused to mount an effective rebuttal, thereby increasing the possibility of a miscarriage of justice. - Wide prosecutorial discretion in plea bargaining

Although plea bargaining as a process is officially recognised in our laws, there is a lack of clarity on how the discretion of the Public Prosecutor (PP) is exercised. As PP, the Attorney General (AG) has the absolute power to prosecute and drop prosecutions. Why are charges in some cases dropped or amended and others not? What are the decisions based on? We need greater transparency. - Limited judicial powers to remedy gross miscarriages of justice post-conviction

A criminal case starting at the High Court ends at the Federal Court as the final court of appeal. But what if there were new evidence that throws fresh light on the conviction? Presently, lawyers file a review application under rule 137, Rules of the Federal Court 1995. However, the grounds on which the court can reopen a case are very narrow. Substantive case reviews – to consider whether a conviction is safe based on new facts – can rarely be done. Legal provisions should be strengthened to allow the highest court to consider cases on their merits and to remedy any miscarriages of justice. - Non-separation of the roles of the AG and PP

The AG is the chief legal adviser to the government. The PP is tasked with prosecuting criminal cases on behalf of the state, even if they were against sitting government ministers. However, there is a perception of conflict of interest or bias when the roles of the AG and PP are fused. The PP’s office should be independent of the government of the day and the AG. Concomitantly, there should be an independent Public Defender’s Office that is adequately funded by the state.

Reform to introduce more effective legal measures for our criminal justice system is sorely needed. The right to a fair trial demands it. The Bar Council should spearhead the reform advocacy. We had discussed many of these issues at Council and committee levels more than ten years ago. They are not new.

The Malaysian government has taken the bold – and correct – step to stop all death executions for over six years now. With a new government and Anwar Ibrahim as Prime Minister (who, incidentally, experienced firsthand the deficiencies of, and injustices caused by, our criminal justice system), the door to substantive law reforms is now open. It is an opportunity the Bar Council should not miss.

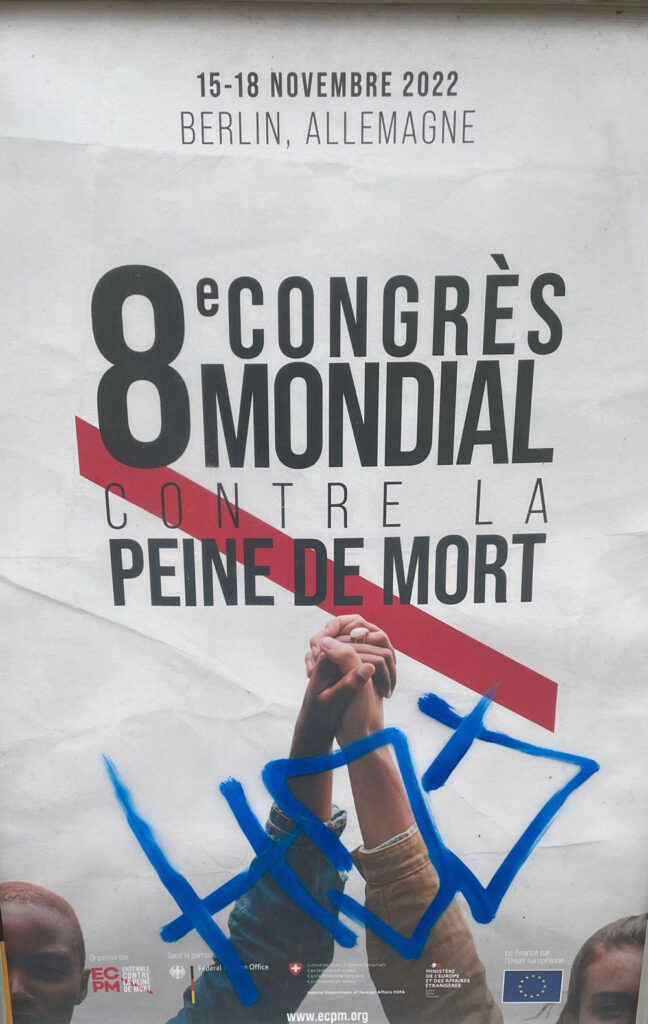

This article is adapted from Edmund’s remarks delivered at the 8th World Congress Against the Death Penalty held in Berlin, Germany from 15 to 18 November 2022. He was asked by The Rights Practice (TRP) to speak on the challenges criminal defence lawyers face in Malaysia.