By Rita Jong | The Heat

Public opinion can be damning. In high-profile criminal cases, the person in the dock is usually presumed guilty until he is proven innocent.

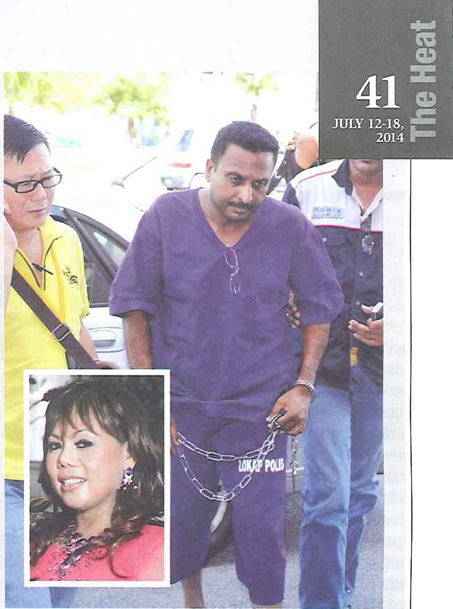

This can be partly attributed to the hype that such cases receive in the media. A picture of a person in handcuffs or that of the victim splashed across the front pages of newspapers can influence public opinion. The perception usually is that the suspect is guilty long before he is fairly tried in court.

When lawyers come into the picture, they are merely discharging a duty to provide proper and rightful representation for the accused. In the process, they are often seen as soulless people who do not have compassion for the victims of the crime.

It cannot be denied that the legal profession is a noble undertaking. After all, it is solely geared towards upholding justice. However, criminal lawyers are more likely to be regarded as cut-throat attorneys who would happily turn their backs on morals for a big payoff.

Even in Hollywood, lawyers are portrayed in a negative light. For instance, in the movie Liar Liar, comedian Jim Carrey plays attorney Fletcher Reede, a compulsive liar who is incapable of telling the truth whether in court or in his personal life. In another movie, The Devil’s Advocate, Keanu Reeves plays hotshot lawyer John Milton who turns his back on ethics just to win and, in the process, turns into Satan himself.

If lawyers are getting such a bad name for taking up criminal cases, why do they still do it?

The role of a defence lawyer

The duty of a defence lawyer is to represent his or her client within the boundaries of the law. His role is to defend his client, no matter how heinous the crime. He is not there to judge his client – that is for the courts to decide. There is solicitor-client confidentiality between lawyer and client; hence, even if the suspect confesses to the crime and insists on bringing the case to trial, the lawyer must ensure his client is given a fair trial.

But more often than not, lawyers place their trust in the legal system and always believe that a suspect or an accused person is “innocent until proven guilty”. They would do what it takes to challenge the prosecution’s case. Because of that, these lawyers are perceived as “protecting” criminals.

The right to be defended

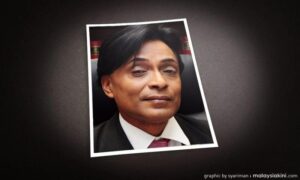

Every person has the right to legal representation no matter what crime or offence he has been accused of committing. Criminal lawyer Sreekant Pillai explains that this right doesn’t change just because a person is charged with a white collar crime, a heinous crime like rape and murder, or a petty theft offence.

“My job is to make sure the law and the Federal Constitution is upheld and that proper procedures are followed. Even if my client had confessed to the crime, I would advise him accordingly and explain the effects of pleading guilty or otherwise,” he tells The Heat.

“But if it involves capital punishment and if my client is not given the option of a lesser charge, I would have no choice but to go for the jugular and challenge the prosecution’s case,” he adds.

Sreenkant, 41, who has handled murder, rape, drugs, firearms, and kidnapping cases, has been in the legal profession for 16 years. He has received his fair share of “evil looks” from friends and members of the public who would ask him why he was doing it.

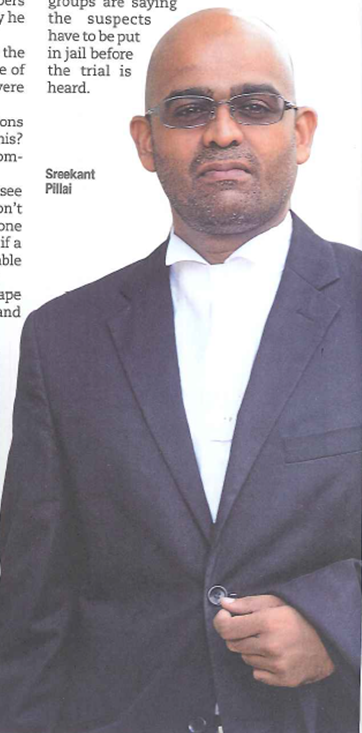

In 2001, when Sreenkant defended the accused in the rape and murder case of Noor Suzaily Mukhtar, his ethics were questioned by friends and strangers.

“People asked me the same questions countless times. ‘How could you do this? How do you feel? Don’t you feel any compassion (for the victim)?’,” he says.

“I can honestly tell you that I don’t see any wrong in what I am doing. I don’t believe in capital punishment and no one should be put to death.” (In Malaysia, if a person is convicted of murder, he is liable to be sentenced to death by hanging.)

Sreenkant says that in rape or child rape cases, there are procedures to follow and that cannot be changed just because emotions are involved or if pressured groups are saying the suspects have to be put in jail before the trial is heard.

To him, defence lawyers are just representing people who need to be defended. “And that is how the system works. Otherwise, we might as well head back to the lawless days when the authorities could just grab you and put you on the rope to be hung without a trial,” he says.

“Then in that case, what happens if an innocent person gets caught? I actually handled a rape case where my client was innocent and his brother who had escaped from police detention was said to have committed the offence.”

Sreekant also says a lawyer’s duty is not just to defend the accused but also to make sure the police have conducted a thorough, unbiased investigation.

He says lawyers cannot be blamed for winning an acquittal for a client. Instead, the police should be blamed for not carrying out proper investigations as it is the lawyer’s duty to challenge the available evidence.

“I have never felt like I was selling my soul to represent clients who told me they did it (the crime). This is my job. I don’t let my emotions get in the way.

“Besides, I am just upholding the law. It is not about ringgit and sen. But if somebody loses his liberty or his life – that’s a lot more at stake,” he says.

All in a day’s work

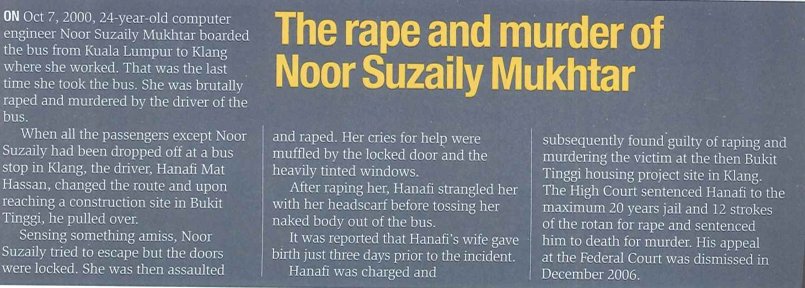

Criminal defence lawyer Amer Hamzah Arshad also believes every suspect has the right to appoint a counsel of his choice regardless of the rime which he or she is alleged to have committed.

“Of course, I get asked the million-dollar question about why I take up certain cases,” says the 41-year-old.

“I defend a suspect with the belief that everyone is equal before the law. There is no difference if the person is charged with a gruesome murder, or a less serious crime. They are all innocent until proven guilty and are entitled to be represented in the court of law.”

He says the public should not associate lawyers with their clients.

“For example, I handled many sexual or rape cases in the past. Lawyers representing the accused in such cases would be frowned upon by the public as lawyers are perceived to be condoning such acts by representing the suspects,” he says.

“Just because lawyers represent suspect charged with such crimes or other offences does not mean they condone such acts. This is a wrong perception and that must be changed.”

He says whether the accused is guilty or not, it is for the court to decide upon hearing evidence. He also had to deal with the “bad guy” stigma when the victims’ family members would shoot him angry looks in court.

Amer, who represented one of the four men accused of murdering cosmetic millionaire Datuk Sosilawati Lawiya and her three aides, had his fair share of name-calling.

“When I handled the case, I was called pengkhianat (traitor) and other names which I prefer not to say. I saw these in forums and chat rooms,” he says.

This, he says, was because in the Sosilawati case, the four victims who were murdered were Malays while the accused were Indians.

“But I am immune to the name-calling now. We can’t control how people think or what people say or write about us,” he says, adding that despite the racial sentiments, Amer insists he made no distinction on colour, as a crime is a crime no matter what race the victim or accused person is.

Sosilawati’s case gripped the nation’s attention because it was exceptionally gruesome. The victims were murdered, their bodies burnt at a farm in Banting, and their ashes thrown in the river.

“We should never allow our personal or political views to cloud our judgement. We have to be professional about it.”

Perhaps, the media is to be blamed for how lawyers are being perceived. Sometimes, media reports so much information about a case and the suspects involved as well as the evidence gathered by the police (which should only be presented in court), resulting in the public forming an opinion against the suspect, branding him guilty.

Amer concurs with this, saying that sometimes, the media splash photographs of suspects in handcuffs and such visual images contribute to the perception of guilt.

But in any event, Amer, who has 15 years’ experience in the legal profession, says instructions given by clients are solicitor-client privilege.

“Whether it really happened or not (the crime), nobody really knows. We need to get facts from the clients and work around it,” he says.

He adds that lawyers should not allow such perceptions to undermine their conscience and moral beliefs.

“I believe that it is the advocate’s role to present the client’s perspective zealously within the bounds of law and ethics. Zealous representation requires subordinating all other interests, including ideology, career, and personal interest, to the legitimate interest of the client.

“I equate being a criminal defence lawyer to being a surgeon in the operation room. His goal is to save the patient. It doesn’t matter if the patient is a good or bad person, a saint or a criminal,” says Amer.

Not a perfect system

Criminal lawyers also do what they do because they are not in support of capital punishment.

In Malaysia where an offence of murder carries the death penalty, Sreenkant says nobody deserves to be sentenced to death or have his liberty taken away from him.

This is because in every man-made system, nothing is perfect.

“There is a saying: it is better to acquit 10 guilty persons than to sentence one innocent man to death, there is no undoing it. The last thing we want is to convict an innocent man. That is why we need defence lawyers,” says Amer.

“The criminal justice system is like a three-legged stool. You have the judiciary, the prosecution and the defence counsel. If you take one leg away, the stool will collapse.”

The murder of Sosilawati Lawiya and three others

Cosmetic millionaire Datuk Sosilawati Lawiya disappeared on Aug 30, 2010, with her driver Kamaruddin Shamsuddin, 44, banker officer Noorhisham Mohamad, 38, and lawyer Ahmad Kamil Abdul Karim, 32.

They were reported missing after they went to a farm in Banting to meet a lawyer to discuss a land deal. Their disappearance made headlines because of Sosilawati, who is the founder of popular cosmetic brand Nouvelle Visages.

A few days later, lawyer N. Pathmanabhan (who Sosilawati was said to have gone to meet at the farm just before her disappearance), and three farm hands – T. Thilaiyalagan, R. Matan, and R. Kathavarayan – were arrested for the crime.

They were subsequently charged with and convicted for the murders of Ladang Gadong in Tanjung Sepat, Banting.

The victims’ bodies were never found. During trial, the court heard that the bodies of the four victims were burnt and their ashes thrown in a river.

The appeal against the conviction is pending at the Court of Appeal.