By Jason Tan and Alan Wong | Off The Edge

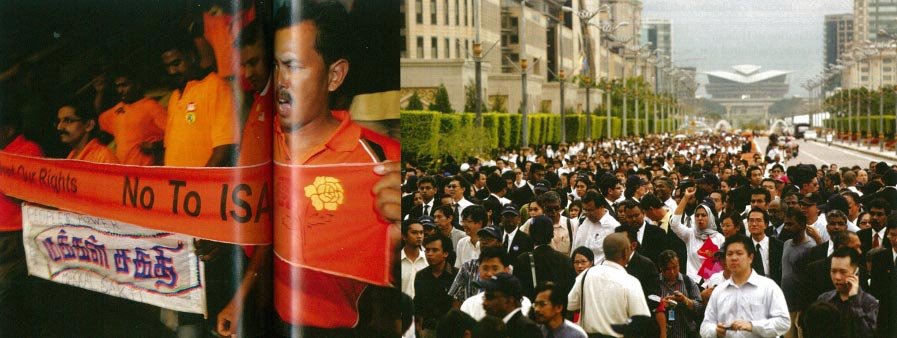

Nobody could say for sure then, but the first Bersih rally in November last year was a prelude to the watershed of March 8, 2008. Tricksy, highly organised and massive, it succeeded despite all official efforts to thwart it. And it had the participation of the Bar Council for the first time in the form of observers from its Human Rights Committee (HRC), whose presence may have kept yet more Malaysians from having their rights tear-gassed and water-cannoned. The HRC has since filed its reports with the Bar Council on the Bersih, Hindraf and the Gabungan Mansuh ISA vigil earlier this year.

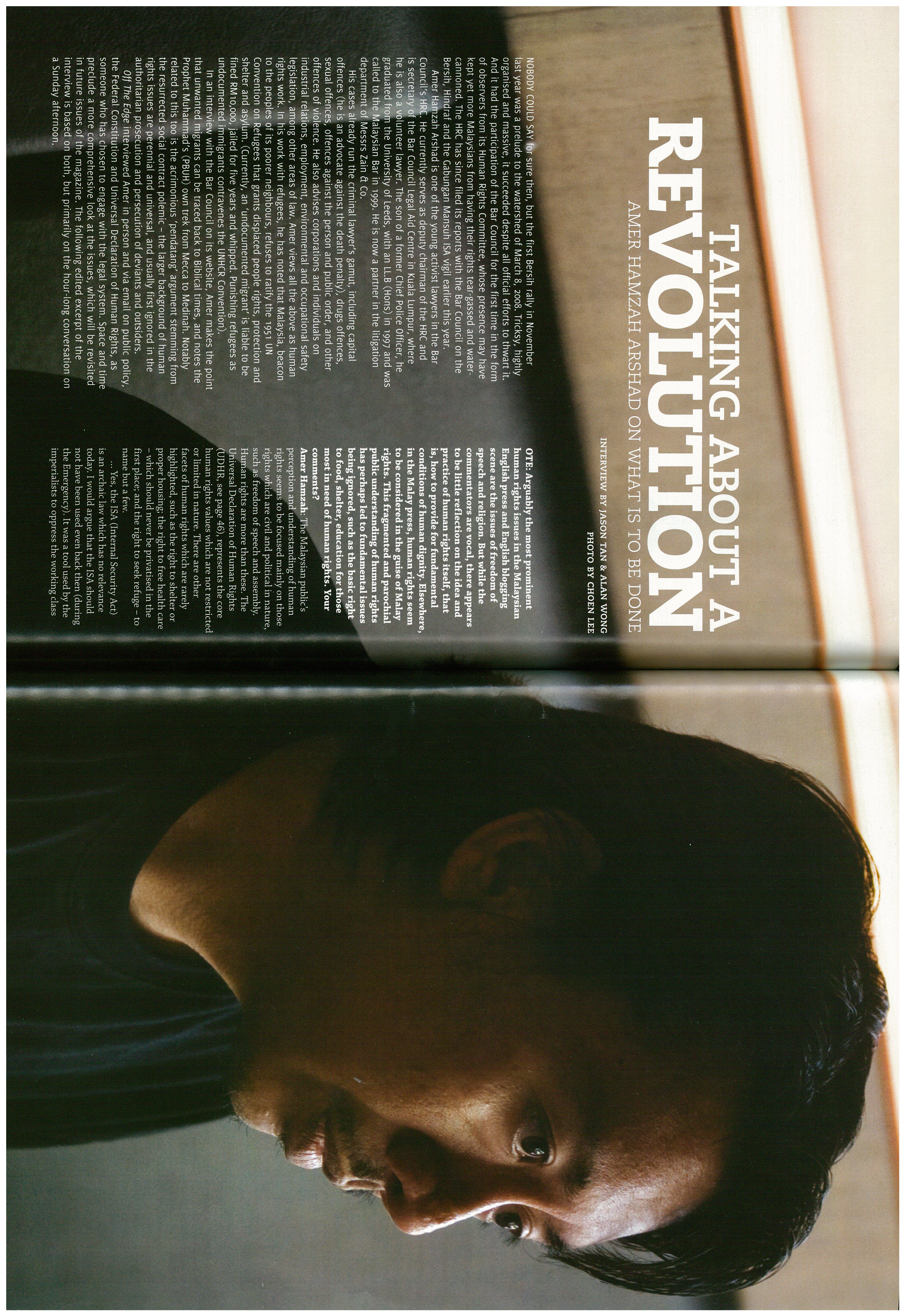

Amer Hamzah Arshad is one of the young activist lawyers in the Bar Council’s HRC. He currently serves as deputy chairman of the HRC and is secretary of the Bar Council Legal Aid Centre in Kuala Lumpur, where he is also a volunteer lawyer. The son of a former Chief Police Officer, he graduated from the University of Leeds, with an LL.B (Hons) in 1997 and was called to the Malaysian Bar in 1999. He is now a partner in the litigation department of Messrs Zain & Co.

His cases already run the criminal lawyer’s gamut, including capital offences (he is an advocate against the death penalty), drugs offences, sexual offences, offences against the person and public order, and other offences of violence. He also advises corporations and individuals on industrial relations, employment, environmental and occupational safety legislation, among other areas of law. Amer views all the above as human rights work. In his work with refugees, he has noted that Malaysia, beacon to the peoples of its poorer neighbours, refuses to ratify the 1951 UN Convention on Refugees that grants displaced people rights, protection and shelter and asylum. (Currently, an “undocumented migrant” is liable to be fined RM10,000, jailed for five years and whipped. Punishing refugees as undocumented immigrants contravenes the UNHCR Convention).

In an interview with the Bar Council on its website, Amer makes the point that unwanted migrants can be traced back to Biblical times, and notes the Prophet Muhammad’s (PBUH) own trek from Mecca to Medinah. Notably related to this too is the acrimonious “pendatang” argument stemming from the resurrected social contract polemic — the larger background of human rights issues are perennial and universal, and usually first ignored in the authoritarian prosecution and persecution of deviants and outsiders.

Off The Edge interviewed Amer in person and via email on public policy, the Federal Constitution and Universal Declaration of Human Rights, as someone who has chosen to engage with the legal system. Space and time preclude a more comprehensive look at the issues, which will be revisited in future issues of the magazine. The following edited excerpt of the interview is based on both, but primarily on the hour-long conversation on a Sunday afternoon.

Arguably the most prominent human rights issues in the Malaysian English press and English blogging scene are the issues of freedom of speech and religion. But while the commentators are vocal, there appears to be little reflection on the idea and practice of human rights itself, that is, how to provide for fundamental conditions of human dignity. Elsewhere, in the Malay press, human rights seem to be considered in the guise of Malay rights. This fragmented and parochial public understanding of human rights has perhaps led to fundamental issues being ignored, such as the basic right to food, shelter, education for those most in need of human rights. Your comments?

The Malaysian public’s perception and understanding of human rights seems to be focused mainly on those rights which are civil and political in nature, such as freedom of speech and assembly. Human rights are more than these. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), represents the core human rights values which are not restricted or limited in nature. There are other facets of human rights which are rarely highlighted, such as the right to shelter or proper housing; the right to free health care — which should never be privatised in the first place — and the right to seek refuge, to name but a few.

…Yes, the ISA (Internal Security Act) is an archaic law which has no relevance today. I would argue that the ISA should not have been used even back then (during the Emergency). It was a tool used by the imperialists to oppress the working class and I think the position is no different now, when it’s used by the ruling government to suppress dissent — Raja Petra (Kamaruddin) is a clear example. People tend to focus on the detention without law issue and forget that there are other rights that are affected by detention without trial, such as the socio-economic rights of the family members of the detainee and the right to education of the kids. Perhaps it’s because the focus of the media has been on the freedom of expression, freedom of movement, that nobody should be detained without trial.

They should expand the human rights discourse beyond civil and political rights. For instance, the right to education is connected to the right to employment, to livelihood and job security. You cannot look at rights in isolation. We should consider human rights holistically. It is good to encourage discourse on those rights, but human rights are not just about freedom of expression, freedom of media… there are other rights as well. For instance, to live in a clean environment is a basic right. You would not want to stay where the air is polluted, and there is no clean water.

So there’s a class divide in the human rights discourse in this country. It’s either that or the issue of Malay rights. Why is it that we can’t seem to present a holistic picture of human rights in this country? How would you try to get some other voices in there?

Let’s look at our education system. We do not have subjects on human rights at primary or secondary levels. Even at tertiary level, it’s an elective subject. [Human rights awareness] is not instilled in the younger generation from the beginning. Perhaps SUHAKAM (the Human Rights Commission of Malaysia) should play a very active role here. If the education system is revamped to instil these values right from the beginning, then human rights will not be perceived as being of alien import.

THE MALAYSIAN MUSLIM-NON-MUSLIM SCHISM

One of the big dangers facing us now is the schism in the public discourse, between Malay Muslims, and non-Muslims and non-Malays. Where do you think the common ground lies where human rights are concerned?

Let’s compare the UDHR and, say, the Islamic [doctrine] of human rights. Some common features are the right to livelihood, the right to life, equality; they’re all there. So why do we say these are Western concepts and therefore not applicable to Islamic communities? I don’t understand the logic behind it. If something is good, it doesn’t matter where it comes from. If we look at the common ground, I don’t think there will be a problem.

It’s going to take more than law to fix that.

Definitely, because you can have the best law in the world, a perfectly drafted piece of legislation — but if you do not have people who can understand and want to implement the law, who don’t want to compromise, what’s the use?

It sounds like what’s happening with our Constitution.

Yes …[but] I am quite optimistic that we can make more headway in terms of human rights, notwithstanding that we have a lot of issues to deal with. There’s always the silver lining.

CIVIL AND SHARIAH HARMONY

It seems inevitable that there has to be some form of accommodation reached between the civil and Shariah court systems, simply because, if we’re talking about multiculturalism, about inter-racial marriages, which in this country would mean inter-religious marriages as well, it is going to be impossible to either put cases into one system or the other…

Prior to 1988, we did not see a lot of these issues being raised, perhaps because the civil court judges back then did not abdicate from doing their duty to uphold the law and the Federal Constitution, regardless of personal beliefs. The law is the law; that is that. Everything is clearly stated in the Federal Constitution.

The problem arises when certain judges decide to push the issues to the Shariah courts to avoid dealing with them. That’s why we now have this conflict between the two jurisdictions. In fact, the one system we have is clear [and can] function perfectly; it depends on the person behind the system — the judges themselves. If they know what they are supposed to uphold, then they should just uphold it. If there is any conflict, how do you expect non-Muslims to go to the Shariah court? The law is very clear on that; the Shariah court doesn’t have jurisdiction over non-Muslims.

What about situations where one partner is Muslim and the other is not?

Logically, based on what we have now, then you have to go to the civil court, because it has jurisdiction over Muslims and non-Muslims. But non-Muslims cannot have recourse to the Shariah court, because you cannot extend its jurisdiction by virtue of consent [of the parties involved] — jurisdiction is only conferred by law. If the jurisdiction of the Shariah court is limited to govern “those professing the religion of Islam” then it should be confined to Muslims. The moment you try to extend it to non-Muslims, then that is where the problem will arise, because the law does not allow you to do so.

So you’re saying that the legal basis is not there for the Shariah court to assume jurisdiction over the non-Muslim parties.

That’s the argument used by those who disagree with Shariah courts having jurisdiction over matters which involve non-Muslims as well as Muslims.

How do you think some sort of rapprochement can be reached between the two systems? The discourse right now is antagonistic.

I think we need to go back to basics to understand the structure of the legal system and the Federal Constitution, and all religions. All the basics must be in place before you move towards a unified system, or whatever system you want.

The civil or Shariah legal system both promote one thing — justice. The problem is that sometimes we are too engrossed with labelling. The moment we hear the words “Islamic” or “secular” we tend to get paranoid. Ultimately — if you look — there are a lot of similarities which we can use to advance human rights and uphold justice. Why do we need to label these as “Shariah” or “civil” court jurisdictions? The focus seems to be on form rather than substance. Whether in Shariah or civil jurisdictions, you’ll still get justice at the end of the day.

The current system, should pose no problems if all of us understand its basic structure. If we talk about a merger of the Shariah law and the Malaysian legal system within the existing framework of the Federal Constitution, we will inevitably come to a stumbling block as our Federal Constitution does not envisage such a situation. What is important in human rights is substance rather than form. What matters the most is the necessity to uphold human rights norms and values regardless of one’s religious belief, colour, race, origin or gender. Ultimately, all religions promote human rights and the well-being of every individual. Of course there are some suggestions that we should set up another court, a constitutional court to decide issues of conflict between jurisdictions, but to be honest whatever court, any system, is only as good as the people implementing it.

THE JUDICIARY

Perhaps it’s a good time to touch on the judiciary which has been besieged by controversy of late, or it may be accurate to say that the issues have come to the surface: The Lingam Tapes, the revelation of Tan Sri Zaki Azmi of his knowledge of corrupt practices and corrupt judges, former Justice Ian Chin’s experiences, and the letter written by Datuk Datuk Syed Ahmad Idid more than ten years ago — accusations of corruption within the Malaysian judiciary are persistent and widely acknowledged but not spoken of by the legal profession for a long time. Having said that, no matter how good the system is, it depends on the people who administer it, what does it mean to you to be practising law under such a system peopled by — from what Tan Sri Zaki has said — are corrupt?

You have to be aware that not all judges are corrupt. There are good judges and bad judges. (pauses) You still have to have some sort of faith in our judiciary.

We cannot run from reality; if you come across corrupt judges, take the necessary action, if you have evidence. You have to go through the entire process.

What I’m getting at is the culture of the rule of law, rather than, say, the culture of being able to select the judges for a favourable result. What do lawyers do when faced with a situation say, that a client has bribed a judge and with the full knowledge of the lawyers concerned?

I think as lawyers we have a duty first and foremost not to the client, but to the law. The problem is when lawyers do not stand up and take up their role to uphold what is right. The judges on their own cannot be corrupted without encouragement from lawyers, for instance. I think it is incumbent upon all of us to take the necessary action. Lawyers who come across instances of other lawyers attempting corruption should report it to the police or the ACA. Small though they may be, they will create a ripple effect and eventually send a strong message…

Is there a sense of resignation though, that this is a job hazard and part and parcel of the system, and there’s nothing you can do, even if you lodge a report with the Police or the ACA?

I won’t deny that there are some who are cynical about reporting instances of corruption to the ACA, and think that they are stuck with the system. But if we keep having this mentality then we should forfeit our rights to criticise the judiciary and the government. We have to act upon the instinct to do the right thing.

As far as the Malaysian Bar is concerned, it has not stopped fighting to restore the credibility of the judiciary since the 1988 crisis. We have campaigned, lobbied, and marched in protest. Some have said that we are fighting a losing battle, but now we see justice being done to the sacked judges, and there’s the setting up of the Judicial Appointment Commission which the Council has lobbying for for years. If it takes more than a decade, so be it. We may not be able to see the fruits of our labour but if the people in the 80’s stopped fighting their causes, we would not be seeing the changes currently in the making.

So it’s quite clear for you what it means to practise as a lawyer under such circumstances, morally…

Yes, under such circumstances the lawyer’s responsibilities are greater. Let’s look at the Legal Profession Act, 1965. Section 42 of the Act is very clear on the Bar’s role in the country, which is “to uphold the cause of justice without regard to its own interests or that of its members, uninfluenced by fear or favour.” What this basically means is that no matter the circumstances we are in, lawyers must be clear of their role [which is] to ensure that justice prevails, even if this means that lawyers have to resort to activism in acts of civil disobedience, such as when lawyers embarked on the Walk for Justice in September 27 last year.

In regards to your peers, though, what if you were aware they indulged in corrupt practices, how would you respond to that?

Fortunately I have yet to come across such a situation. If I did, [I would] lodge a complaint with the disciplinary board, for instance. You can’t just close one eye just because you are a fellow lawyer. You keep telling the public that you have to lodge a report when you come across corruption yet when it comes to one of your own members, you just keep quiet. I just can’t fathom that kind of attitude.

When it comes to the cost, though… you hear anecdotes of lawyers who have resigned from their firms because of what they have witnessed…

They should. As a matter of fact I know someone who is resigning because of such allegations as well. And I think it is the right thing to do; you shouldn’t be working at an outfit that indulges in corrupt practices. And if there’s concrete evidence, stern action should be taken against these lawyers and firms that indulge in corrupt practices.

But of course you would encourage that person to make a report?

Yes, definitely. Of course, there will be problems and setbacks, but you shouldn’t be demoralised by that. The right thing to do is the right thing to do. There are no two ways about it.

If we now try to reform the judiciary, and prosecute corrupt judges and lawyers, and even clients, what would be the practical implications of that?

Well… immediately, of course, the image of the judiciary will suffer in the midst of such revelations. News of the arrests of corrupt judges and lawyers and prosecutors will cause the public to lose confidence in the judiciary and the entire justice system. But it is only through this painful process that we can start afresh and rebuild. Whether we like it or not, there are practical implications: cases can be compromised and affected parties will want cases to be reopened… Yes, it will be quite a task but we have to do it.

Of course, there will be counter-arguments such as, why are you trying to disrupt something that is going on perfectly? Why not just ignore it? But if someone has been wronged, don’t they deserve justice at the end of the day? The party who was legally entitled to a certain right or remedy was denied of that by corrupt judges — shouldn’t he be allowed to have his case re-looked by a different, impartial panel based on merits and not by who pays more?

‘HUMAN RIGHTS LAWYER‘

Let’s talk about your experience as a human rights lawyer and the attitude of your peers. What kind of response do you elicit when you bring up issues of human rights and class divides?

Even among the legal fraternity, it seems to be something which is… relatively new [despite] the various rights enumerated in our Constitution: freedom of expression, freedom of association, right to life… As lawyers it is our duty to uphold these rights because they are enshrined in the supreme law of the land. Otherwise, you have this document with all these pious platitudes, that you cannot translate it into reality.

So to say human rights are something that is alien — to me it’s a bit puzzling. Unfortunately, most lawyers tend to adopt the pragmatic approach — “Does getting involved in human rights cases bring in a lot of money?”… That is why you don’t see a lot of lawyers involved in rights cases.

Let’s take another angle — criminal law. People think criminal law exists because of criminals. But criminal law is also a part of human rights issues, such as the right to representation and access to justice. But I think they (lawyers) don’t see it from that angle; they think, “you’re paying me and therefore I represent you”. But the moment you start analysing it, everything has a human rights angle. Civil matters, for instance, also involve human rights such as the right to livelihood… So the issue of human rights is not something that should be alien to lawyers. Unfortunately, because we aren’t trained or educated in human rights language, we tend to think that human rights is only focused on limited issues.

Human rights are for people with too much time on their hands.

(laughs) Well, I have to admit that, yes, initially you do get that kind of feedback from lawyers. Take legal aid for instance. Legal aid is a form of access to justice, a fundamental right. But when lawyers start getting involved in legal aid and taking on pro bono cases, it’s not uncommon for them to receive remarks such as “Eh, you don’t have any work to do, is it? Are you not getting enough work?”

And it’s related to the economy and opportunity cost…

Agreed. That is always the criticism of getting involved in human rights cases.

It’s a systemic problem…

…because we don’t have a state-funded legal aid. If we did, legal aid cases can generate income too. The UK for instance, sets aside funds for legal aid, so you’ve got big names like Geoffrey Robertson, top QCs (Queen’s Counsel) taking up human rights cases — and paid through the legal aid scheme. By having state-funded legal aid, you encourage more lawyers to take up issues that affect the ordinary citizen.

An important right which is not well publicised here is the issue of access to justice. Article 5(1) of the Federal Constitution states that no person shall be deprived of his life and liberty save in accordance with the law and Article 8(1) talks about equality before the law and equal protection before the law. In reality, the working classes are often left with no adequate recourse to justice. A poor person who is charged with a criminal offence may have difficulty in engaging a lawyer as compared to a rich Dato’ or Tan Sri, for instance. This issue begs the question whether we have an adequate legal aid scheme for the poor. At the moment, there are the government legal aid bureau, the Bar Council Legal Aid Centre and the court-assigned counsel scheme, but they are far from adequate. We do not have a proper and comprehensive state-funded legal aid scheme in this country; we do not have a public defender’s department. All these are important human rights issues but they rarely get the attention they deserve.

The government’s legal aid bureau is governed by the Legal Aid Act and its jurisdiction is very much limited to assistance for civil and family law matters; and when it comes to criminal law matters, its assistance is limited to juveniles. In cases where the accused intends to plead guilty, it assists only in mitigation.

And for those who claim trial, [except for capital offences], there is no assistance afforded to them under the government’s legal aid bureau. That’s where the Bar Council’s Legal Aid Centre comes into the picture. The Legal Profession Act requires the Bar Council to set up a scheme to help the poor and the impecunious, and we do take up criminal cases for those who cannot afford legal representation. Most of them fall into the lower class or the lower-middle class categories. The Bar Council Legal Aid Scheme is purely voluntary in nature, so lawyers contribute RM100 every year into a legal aid fund used to run the legal aid centres throughout the Peninsula: one in KL, Selangor, Perak, Penang…

Legal assistance is given by lawyers on a pro bono basis. And that’s where the problem is, pro bono: some say, “Corporate cases generate more income, so why should I spend my time doing pro bono?” But if we had a proper state-funded legal aid scheme, perhaps there would be more lawyers involved in legal aid. (The Bar Council reportedly handled 18,000 cases last year for which legal fees waived amounted to RM100 million.)

LATE ON-SET LEFTISM

And your left-leaning tendencies, where do they come from?

(laughs) I think that when you deal with people on the ground, you tend to see injustice. Take the right to shelter, basic needs like that are still not available to some people. The current system that we have doesn’t seem to provide for all, only the few that benefit from it. Doesn’t matter what you call it, the New Economic Policy or whatever, it does not seem to help the poor and marginalised. I think it’s through that process one becomes aware that there are certain things that require state intervention.

So you didn’t start out “like that” but it’s only along the way as you practised…

Yes, I would say so. Of course initially there was the negative propaganda that if you’re communist or socialist, then you are anti-religion and whatnot…

Do you face that kind of stigma?

Admittedly, there are those who are cynical and say that doing human rights cases is a waste of time. There are others who also question you as to why you would represent someone who is charged with a heinous crime or represent someone who has been detained under the ISA for allegedly being a terrorist etc. At times you may receive threats. But I cannot stop people from having such prejudices on these usually controversial issues. Yet at the same time, we should not allow this mindset or culture to spread.

Lest we forget, in the late 1940s till the late 50s in the US, lawyers were put off defending alleged communists who faced congressional witch-hunts initiated by US Senator Joseph McCarthy. Such fear had made it impossible for lawyers who supported civil liberties and constitutional rights to defend and represent those who were accused of being communists without risking their lives, families or careers. We should not create a situation here where lawyers or human rights activists are condemned or put to fear for defending human rights.

(Quotes Malcolm X) “I’m for truth, no matter who tells it. I’m for justice, no matter who it is for or against. I’m a human being first and foremost, and as such I’m for whoever and whatever benefits humanity as a whole.”

You have to make it clear to the people that when we talk about being left or socialist, it’s more in terms of economic issues, the means of production — who controls those means for the benefit of society — that is the thrust of it. You aren’t focused so much on “do you take up arms.” I mean, look, in any revolution or fight you have to take up arms, even back then.

Perhaps be up in arms over issues…

Yes. As long as you can do your work within the system, that should be the first option. When that option fails, I think sometimes you have to… take more [activist] measures.

So, Malaysian legal system — reform?

I wouldn’t say “reform” — we should have a revolution in our legal system. A revolution of the mindset: lawyers, judges, all of us have to go through it… If we are living in a country which is governed by an oppressive and corrupt regime, then the only option available to the subjects is to demand for a change by way of a revolution. By way of an analogy, if we have a corrupt judiciary, then, the only way out is for lawyers and the stakeholders in the Malaysian justice system to initiate a judicial and legal revolution… Our legal education, for instance has to undergo a transformation. Education is crucial to any system.

You’re talking about a lost generation.

Yes, when we do not encourage people to think analytically or to discuss, or disagree with the lecturer’s views — you can see the symptoms now. And the worst affected seem to be…

Basically, the people who man the democratic institutions…

You have to empower the masses. The March elections are a clear example. The problem is starting something and not being able to finish it.

Starting a revolution is easy…

This article was reproduced by LoyarBurok. Archived at Perma.