By Beh Lih Yi | Thomson Reuters Foundation

A Malaysian court that promised justice for victims of human trafficking made eight convictions in its inaugural year despite the launch of hundreds of investigations in recent years, data obtained exclusively by the Thomson Reuters Foundation revealed.

Malaysia is a magnet for traffickers due to its heavy reliance on foreign workers, many lured from nearby Indonesia and Bangladesh with promises of honest work but ending up trapped in unpaid labor, debt and facing exploitation.

Malaysia is home to an estimated 212,000 of about 40 million people trapped in slavery worldwide, according to the Global Slavery Index by human rights group Walk Free Foundation, and the government has vowed to act and amend labor laws.

Yet the Southeast Asian nation only secured 140 human trafficking convictions between 2014 and 2018, despite launching more than 1,600 investigations and identifying almost 3,000 victims, according to the U.S. Trafficking in Persons reports.

Seeking to boost these numbers, the Southeast Asian nation launched a special trafficking court in March 2018 – in a bid to speed up the pace of justice and raise public awareness.

But official figures obtained exclusively by the Thomson Reuters Foundation from the court’s registrar office showed that only 26 cases were cleared in the court’s first 15 months – with eight resulting in a conviction.

“What happened to all the promises?” asked Aegile Fernandez, an anti-trafficking campaigner and director at the Kuala Lumpur-based migrant rights group Tenaganita.

A judiciary spokeswoman declined to provide further details of the cases. It was not clear what punishments were meted out.

Law minister Liew Vui Keong and the Attorney-General’s Chambers, which oversees prosecutions, did not respond to questions about the court’s effectiveness or plans for the future. Liew’s press officer said justice takes time to obtain.

“Do you know when the court was set up? Do you want me to enlighten you how long a trial can go on?” Samantha Chong said in a text message to the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Comparatively, a court on sexual crimes against children set up in mid-2017 saw 367 cases cleared in the first year, the court website showed, without giving conviction numbers.

War declared

The U.S. State Department’s 2019 Trafficking in Persons report put Malaysia in its penultimate rank – out of four categories – for measures undertaken to fight human trafficking.

A downgrade to the lowest ranking can trigger U.S. sanctions which Washington imposed on 21 nations in this year’s report.

The trafficking court was initially welcomed by activists concerned that most victims toiling in factories, selling sex or working as domestic staff, were foreign nationals reluctant to fight their case due to the time it takes and lack of support.

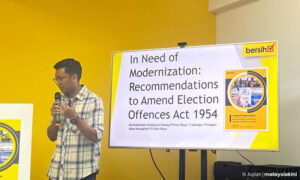

Malaysia’s low conviction record highlights gaps in its anti-trafficking law since an offense can only be proven if there was physical coercion, said human rights lawyer Edmund Bon from AmerBON Advocates, who is lobbying to change the law.

Due to the legal constraints, workers forced into excessive overtime or coerced to relinquish their passports are often treated as immigration or industrial dispute cases, and not heard in the special court, Bon added.

“That has to be amended because trafficking can be by way of emotional duress, it can be psychological,” said Bon, formerly a government-appointed human rights envoy. “There are a lot of people who get off prosecution because of the definition.”

Malaysia relies on about 2 million registered migrant workers for jobs on plantations, in factories or construction.

But many others work without permits leaving them at the mercy of human traffickers to whom they owe money for transport to Malaysia where they were promised jobs.

Indonesia and Cambodia have in the past temporarily banned their citizens from going to work in Malaysia after cases of abuse surfaced but those bans have both been lifted.

“There are a lot of cases and it’s a big crime in Malaysia, but the very fact that we don’t identify these cases as trafficking is why we see a very low conviction rate,” said Fernandez of rights group Tenaganita. “We are asking: ‘why?’”