By Annabelle Lee | Malaysiakini

The tail end of Malaysia’s controversial 2021 emergency has been nothing short of dramatic.

First, a stunning royal rebuke over the emergency ordinances. Then, the prime minister’s insistence that the Yang di-Pertuan Agong has little choice but to revoke them as advised.

Some are now describing this as a constitutional crisis between the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) and Istana Negara.

Here, Malaysiakini recapitulates what happened and sheds light on key questions involving the still-evolving situation. This explainer relies on the Federal Constitution, lawyers and political analysts.

What triggered this?

On July 26, the first day of the long-anticipated Dewan Rakyat session, de facto Law Minister Takiyuddin Hassan claimed the cabinet had already revoked all emergency ordinances.

The second part of the surprise was when he alleged this was done back on July 21 after a cabinet meeting.

Many questioned why there was no Gazette on the matter, whether the Agong had in fact assented to the revocation, and why a five-day delay in announcing such an important matter.

Why was the Agong ‘very disappointed’?

Three days later, the Agong said Takiyuddin had “misled” the Dewan Rakyat with his “inaccurate” claim that all emergency ordinances had already been revoked.

The Agong said he had yet to assent to any revocation.

During an emergency, the Agong has the power to promulgate or enact ordinances. He also has the power to revoke them, the palace said. [Article 150(2B) and Article 150(3) of the Constitution]

An ordinance is a rule enacted under an emergency. Unlike a law, it is not passed in Parliament.

Constitutional Law professor Shad Saleem Faruqi underscored that no revocation is accomplished unless the Agong signs the order, and the order is gazetted.

His Majesty was also upset that Takiyuddin and Attorney-General Idrus Harun had failed to comply with his request to have the ordinances debated in the Dewan Rakyat.

The seven ordinances are:

1. Emergency (Essential Powers) Ordinance 2021

2. Emergency (Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases) (Amendment) Ordinance 2021

3. Emergency (Employees’ Minimum Standards of Housing, Accommodations and Amenities) (Amendment) Ordinance 2021

4. Emergency (Essential Powers) (No 2) Ordinance 2021

5. Emergency (Essential Powers) (Amendment) Ordinance 2021

6. Emergency (Offenders Compulsory Attendance) (Amendment) Ordinance 2021

7. Emergency (National Trust Fund) (Amendment) Ordinance 2021

So what is the proper process?

Based on Article 150(3) of the Constitution, lawyer Mohamed Haniff Khatri said there are two ways to get rid of emergency ordinances.

The first way is for the Agong to revoke them.

The second way is for ordinances to be voted down and annulled after they are laid before the Dewan Rakyat and Dewan Negara.

Why are people calling this a constitutional crisis?

In response to the palace, the PMO insisted that the Agong is constitutionally bound to accept the cabinet’s advice on a matter and act in accordance with it. [Article 40(1) and Article 40(1A)]

This is regardless of whether or not the Agong agrees with the advice.

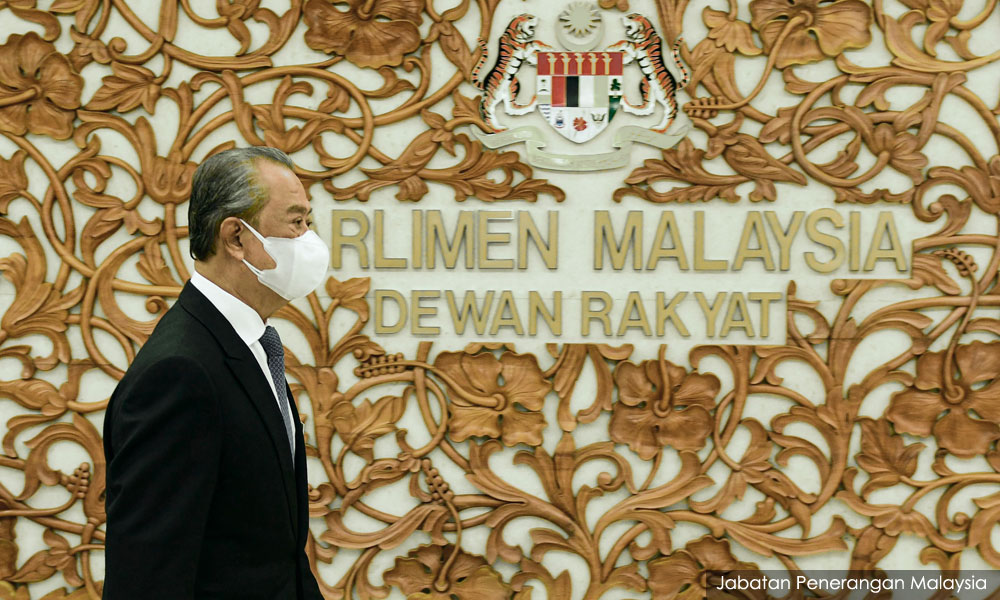

On July 23, before the special parliamentary session began, Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin had advised the Agong to revoke all emergency ordinances and backdate the revocation to July 21. He advised the Agong a second time on July 27.

Herein lies a tussle over the scope of the Agong’s discretion.

The Agong has specifically instructed for the ordinances to be debated in Parliament, rather than be revoked.

While acknowledging the Agong’s constitutional obligation to act on the executive’s advice, the palace maintained His Majesty is also duty-bound to speak out against “unconstitutional” moves.

Did Putrajaya violate the Constitution?

The PMO argued that it acted in accordance with the Constitution in advising the Agong to revoke the ordinances.

It also said it adhered to Article 150(3) by laying all ordinances before both Parliament houses. The article stipulates that Parliament can annul ordinances “if not sooner revoked”.

“The government is of the view that all actions were done in an orderly manner and in accordance with provisions in the law and the Federal Constitution,” said the PMO.

Dewan Rakyat speaker Azhar Azizan Harun previously defended the government’s move to not put the ordinances to a debate. The former lawyer noted there is no constitutional requirement for ordinances to be debated or voted upon.

He said Article 150(3) stipulated that ordinances must simply be “laid” but did not specify they had to be “tabled”.

Why not just put it to a vote?

Perikatan Nasional (PN) is seen to be reluctant to do so as a vote will test Muhyiddin’s tissue-thin majority in Parliament and thus his legitimacy as prime minister.

Chief of its concerns are MPs loyal to Umno president Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, who has repeatedly indicated that they are against the government despite their party being part of the PN coalition.

However, without any proof of revocation, political analyst Wong Chin Huat opined that the ordinances cannot bypass Parliament.

Opposition MPs have repeatedly demanded the emergency ordinances be debated and voted upon.

Where did #KerajaanDerhaka come from?

It is unusual for the palace to speak out so strongly against the government of the day.

Derhaka means treason or treachery. The word is typically used in reference to perceived disrespect against the monarchy.

Political analyst Awang Azman Awang Pawi noted that the Agong’s use of the words “amat dukacita” (very disappointed) pointed to a lack of respect by PN. More so, when the Agong reprimanded Takiyuddin and the AG for their defiance to allow the ordinances to be debated as His Majesty had requested.

Following Agong’s statement, the #KerajaanDerhaka hashtag took flight on Twitter.

To resolve the issue, political analyst Muhamad Nadzri Mohamed Noor proposed that the Dewan Rakyat’s Rights and Privileges Committee mete out disciplinary action against Takiyuddin.

There have been calls, including by a faction of Umno, for Muhyiddin and his cabinet to apologise and resign over the incident. Some Umno leaders have urged the party to push for an “interim government”.

How has PN responded to the backlash?

PN parties have closed ranks and underscored Muhyiddin’s legitimacy.

The PN women's wing said the ruling coalition supported the constitutional monarchy and would never go against the Agong.

Bersatu deputy president Ahmad Faizul Azumu voiced the party’s “undivided support” for their president.

Deputy Prime Minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob of Umno insisted PN had “more than 110 MPs” on its side in the Dewan Rakyat. He later claimed 40 BN lawmakers backed Muhyiddin.

PAS, meanwhile, said it backed the PM as well as all cabinet’s decisions. Party president Abdul Hadi Awang also dismissed critics who he claimed were threatened by PN’s “ability to solve the country’s problems”, while another PAS leader downplayed the controversy, describing it as a minor issue.

GPS called for political stability and said it supported the constitutional monarchy system.

What becomes of the ordinances?

Unless they are somehow revoked, professor Shad pointed out that the ordinances will remain in force for up to six months (Feb 1, 2022) from the day the emergency ceases - Sunday, Aug 1. [Article 150(7)]

That is unless the Dewan Rakyat votes to annul them. Thus, he said there is still cause to debate the ordinances.

“Ordinances can and should be discussed, debated, and if need be, annulled by Parliament. Or they could be revoked by the Agong,” he told Malaysiakini.

Lawyer New Sin Yew argued that Parliament should vote on the ordinances.

“If Parliament votes to annul, then they cease to have effect immediately. No need to wait for the six-month period to lapse,” he said.

Will ordinances finally be debated and voted on this Monday?

Maybe.

Monday (Aug 2) is the final day of the special Dewan Rakyat sitting. Takiyuddin is scheduled to explain his controversial announcement about the revocation of the emergency ordinances.

However, the discovery of 11 Covid-19 cases within Parliament grounds threatens to derail the much-anticipated session.

Following Agong’s reprimand, Thursday’s sitting was adjourned four times and ultimately suspended until Monday. Parliament was then placed under a surprise lockdown for a round of Covid-19 testing.

The timing led Port Dickson MP Anwar Ibrahim to call this a “ruse” to prevent the Dewan Rakyat from debating the controversy.

The opposition leader revealed he had just submitted a no-confidence motion against the PM.