By Emily Ding, Charis Loke, Ellena Ekarahendy | New Naratif

In October 2018—just months after Malaysians voted out the coalition that had been in power since 1957—Liew Vui Keong, the new head of the Legal Affairs Division in the Prime Minister’s Department, announced that the death penalty would be completely abolished for all offences in the country.

In January 2019, at an emotional meeting with families of death row inmates, he said, “I believe that if you believe killing is wrong, then you cannot support the government doing it.”

But pro-death penalty voices—including opposition party members, former police chiefs, and lawyers—have emerged. Public outrage over violent crimes such as the death of a nine-month-old baby as a result of rape and abuse, allegedly by the child’s caregiver’s husband, has also fuelled such views.

Proponents of retaining the death penalty argue that it acts as a powerful deterrent against criminal activity, despite the absence of such evidence. They also argue that those who have violated the sanctity of life deserve to pay for their crime by losing their own life

The Malaysian government has since appeared to have back-pedalled. Instead of complete abolition, Deputy Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department Mohamed Hanipa Maidin announced that the mandatory death penalty for 11 criminal offences—including terrorism, murder, and hostage-taking—would be repealed. Instead, judges would be given the discretion to decide whether to impose the death sentence. Speaking to the media, Liew still did not rule out abolition, but said that it was merely one of the options on the table.

The announcement has come as a disappointment to Malaysian abolitionists. Some argue that even if one were to agree that “an eye for an eye” is an appropriate principle to abide by in a criminal justice system, one should consider the possibility of wrongful convictions and executions.

“It’s commonly accepted around the world that no legal system is perfect. Mistakes happen,” says Amer Hamzah, one of Malaysia’s most prominent criminal defense lawyers. “In any legal system, you could be sending innocent people to death. That’s an irreversible act. Do you really want to take that chance?”

“But when you tell people that, they say, ‘Show me one case,’” says Ngeow Chow Ying, a lawyer who actively campaigns for the abolition of the death penalty. An extensive public opinion survey commissioned by the Death Penalty Project in 2012 found that support for the death penalty would fall significantly if it could be proven that innocent people have sometimes been executed.

The problem: it’s difficult to prove a wrongful execution in Malaysia. “Wrongful convictions” don’t exist in Malaysia’s legal vocabulary. That doesn’t necessarily mean that such errors don’t happen; it’s just that Malaysia offers extremely limited avenues to re-examine cases once they’ve already exhausted the appeals process.

“It’s a well-established idea that all legal proceedings must have finality,” Amer says. But are there exceptions?

The case of Mainthan Arumugam

The story of an inmate currently languishing on death row—metaphorically called bilik akhir in Malaysia, which translates to “last room”—highlights the possibility of wrongful convictions in Malaysia.

On 9 August 2004, Mainthan Arumugam, a scrap metal trader who lived and worked in the Pandan Indah neighbourhood in the state of Selangor, received a call from Muniandy Nadeson—a fellow trader he’d known for about ten years.

Muniandy said that he’d finally found his sister-in-law, who’d run away about three weeks ago with a man named Manivanan Vellaysamy. She and Manivanan had been spotted together in the neighbourhood.

The two men picked up the couple and brought them back to Mainthan’s home, 50m away from his scrap metal store. Muniandy later brought his sister-in-law home with him. From that point on, accounts as to Manivanan’s subsequent whereabouts diverge.

The next day, a human head and a pair of arms, severed and burnt, were found in a grass clearing about not far away from Mainthan’s house and store. DNA tests appeared to show that the body parts belonged to the same person.

Muniandy’s sister-in-law identified the body parts as belonging to Manivanan. According to the pathologist, she identified the remains based on the rings on the fingers—one inscribed with the word “Love”—and the colourful strings tied to one wrist. She claimed they were gifts she had given him, the pathologist said.

But instead of confirming the victim’s identity as Manivanan, the fingerprint test identified the remains as belonging to an Indian national by the name of Kalidash Arumugam. A few days later, a torso wrapped in plastic and a pair of legs were found in a sewage tank in the area.

Although their accounts conflict in certain aspects, two witnesses claimed they saw a bloodied body lying on the floor of Mainthan’s shop the evening before, where he and a few other men had been drinking liquor to celebrate a colleague’s birthday.

Later, along with three other accused, Mainthan was charged with the murder of Manivanan Vellaysamy.

Mainthan’s conviction and death sentence

When his defence was called upon in the High Court of Shah Alam, Mainthan said that the bloody man the two witnesses had seen was a drug addict named Devadass Suppiah, who sometimes worked for him. Mainthan had suspected Devadass of stealing from his premises, and had beaten him with a rattan cane and an iron weight; two other men had also beaten Devadass, he said. But they did not kill him.

Mainthan said he didn’t know who the found body parts belonged to, but they couldn’t have belonged to Devadass. After beating Devadass that day, he said he’d asked one of Devadass’ relatives to send him to Kuala Lumpur General Hospital for treatment. He said he’d seen Devadass once after that day, walking past his store with his wife and child. As far as Mainthan knows, Devadass is still alive.

However, Devadass was never brought to testify in court, as Mainthan and his lawyers had been unable to contact him. In the end, the High Court judge ruled that Mainthan’s defence was an afterthought and a concoction. Even though the DNA of the two sets of remains differed, the judge accepted expert testimony that the discrepancy could be attributed to the deterioration of the specimens due to being submerged in water for a period of time, and found that the two sets belonged to the same person. The judge also determined Manivanan and Kalidash to be one and the same person. In the end, Mainthan and his three co-accused were convicted of Manivanan Vellaysamy’s murder and sentenced to death.

During the appeal stage in the upper courts, Mainthan’s lawyers raised doubts about the identity of the victim—one of the ingredients of the crime of murder that has to be proven. They argued that it was not clear that any of the recovered body parts actually belonged to Manivanan. The DNA of the two sets of body parts differed, and the prosecution had been unable to locate Muniandy’s sister-in-law herself to testify at trial as to the victim’s identity.

Despite this, the Court of Appeal and the Federal Court affirmed the High Court’s findings, and upheld Mainthan’s conviction and death sentence. However, the Federal Court found that the prosecution had failed to establish enough evidence against Mainthan’s three co-accused, and acquitted them.

Mainthan has since submitted a plea for clemency to the pardons board, but has yet to hear back. He’s now 48 years old, and has been in prison for 14 years. He continues to maintain his innocence.

Applying to the Federal Court for review

Having exhausted the appeals and pardons process, the only other avenue left to Mainthan to reopen his case is to apply to the Federal Court for review.

As Malaysia’s highest court, the Federal Court has the inherent power to “hear any application or to make any order as may be necessary to prevent injustice”, according to law. But Abdul Rashid Ismail, formerly of the National Human Rights Society (HAKAM), points out that the Federal Court has stated in past judgements that it’ll only review cases that fall within “limited grounds and very exceptional circumstances”. In the past, the Federal Court has rejected even applications in which new evidence had come to light as they do not meet the threshold required.

Mainthan’s case is one such example. The court has declined to reopen his case twice, most recently in August 2017, after it appeared that Devadass was both real and very much alive. He had made a surprise appearance at the funeral of Mainthan’s mother in March that same year.

In Devadass’ signed affidavit supporting Mainthan’s application for review, he said that he’d only learnt about Mainthan’s being on death row at the funeral. He confirmed that Mainthan had beaten him up that night, that he had been subsequently brought to the hospital where he received stitches. He said that after that incident, he’d moved to another state without telling Mainthan and his family. He’d ignored their calls because he was afraid and did not want to see them.

But Devadass’ affidavit failed to convince the Federal Court to review Mainthan’s case.

“I think this is one example where the miscarriage of justice may have happened,” says lawyer Joshua Tay, who assisted Amer Hamzah on Mainthan’s review application. “It’s important that the new evidence about the mistaken identity of the victim should be considered by the Federal Court. Whether there is merit with regards to that issue is secondary. However when there is new evidence which surfaces after the trial and the appeal stage, there must be some kind of legal avenue to reopen the case. That’s only fair.”

Rashid agrees, especially in cases where individuals are facing life and death. “Part of the Court’s concern is that they do not want cases to be re-filed over and over. But they cannot worry about opening the floodgates all the time.”

The lack of an independent review body

With the Federal Court unwilling to reopen Mainthan’s case, there are no more options left to him to prove his innocence. Unlike some other countries, Malaysia lacks a dedicated organisation to review cases in which the miscarriage of justice is suspected to have occurred.

The Innocence Project, for instance, began its work in the United States, but has since spread to other parts of the world. In Asia, only Taiwan is part of its network.

“Actually, before the Taiwan Innocence Project was founded in 2012, we already had an avenue for retrial; and in 2015, the Criminal Procedure Code was revised to adopt a slightly looser definition of ‘new’ evidence, which includes new analysis of the same evidence that was presented at trial,” says Communications Director Ko Yunching.

“But it can still be difficult to reopen a case, especially for those who don’t have the financial resources to pursue it. For this reason, the Taiwan Innocence Project was founded especially to investigate suspected wrongful convictions. We provide our services pro bono, and we are funded by donations and foundation grants.”

So far, the Taiwan Innocence Project has taken up the cases of 26 convicted, two of them for murder. One has been exonerated, while the other’s case is still pending.

In the United Kingdom, from which Malaysia inherited its legal system, there’s also the Criminal Cases Review Commission—an independent body which looks into suspected miscarriages of justice and decides whether to send them back to the Court of Appeal for review. Malaysia has no equivalent body; last May, Lawyers for Liberty—a group of lawyers promoting human rights—called for the establishment of a similar commission in Malaysia.

Ko admits that there is a risk, of course, in taking up the crusade of exonerating the innocent. “All these cases have been finalised. A lot of judges have reviewed them and found the accused guilty, and we are only an NGO and yet we want to overthrow these decisions,” she says.

“There is always the risk that we might be rescuing the wrong person. And there is always the risk of executing the wrong person. In the end, it’s a kind of balance we have to tread.”

None of the lawyers and activists who have taken an interest in Mainthan’s case are saying that he’s innocent. What they are saying is: based on all the available evidence, Mainthan cannot be said to be guilty of the murder of Manivanan Vellaysamy beyond reasonable doubt. “It’s one of the more persuasive cases I’ve seen in a while,” says Amer Hamzah.

The government’s deliberations on the death penalty have given Mainthan and his family some hope, though Mainthan’s wife Gunalakshmi Karupaya tells me she’s careful not to get his hopes up when she visits him every week.

“In fact, he’s the one who’s being positive. He tells me not to worry,” she says, when we meet in her house in Pandan Indah. Previously a homemaker, she had to start working 10 years ago to raise their four teenage children on her own. She currently works as a cleaner in a school.

With the help of family, friends, and activists, she does what she can to raise awareness of Mainthan’s case—approaching ministers of parliament and talking to the media. Mainthan’s story has also been made into a short documentary, Menunggu Masa, by lawyers Seira Sacha Abu Bakar and Sherrie Razak Dali.

The possibility of making mistakes

In the absence of independent bodies reviewing cases and investigating potential wrongful convictions, perhaps the number of convictions by the lower courts that have been overturned by the higher courts can give an idea of the imperfection of Malaysia’s legal system.

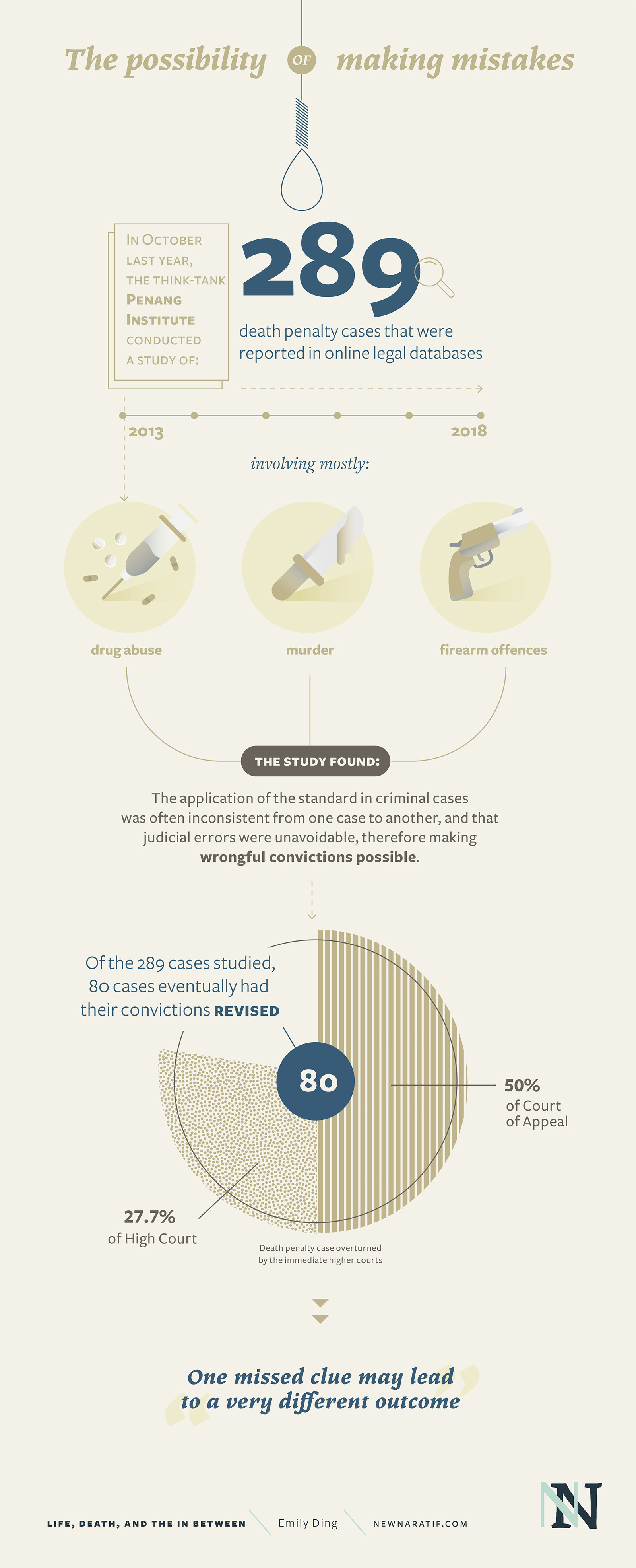

In October last year, the think-tank Penang Institute conducted a study—co-authored by lawyer and anti-death penalty activist Ngeow Chow Ying—of 289 death penalty cases that were reported in online legal databases between 2013 and 2018, involving mostly drug trafficking, murder and firearm offences.

It found that the application of the standard in criminal cases—that judges must be satisfied beyond reasonable doubt that the person accused is guilty of the crime—was often inconsistent from one case to another, and that judicial errors were unavoidable, therefore making wrongful convictions possible.

Of the 289 cases studied, 80 cases eventually had their convictions revised. On average, 27.7% of High Court and 50% of Court of Appeal death penalty case judgements were overturned by the immediate higher courts. In most cases, the accused raised a defence based on arguments of evidence, not legal technicalities. According to the study, “One missed clue may lead to a very different outcome.”

There are many reasons mistakes could be made. The study cites the use of torture to exact confessions, corruption, the admission of contradictory evidence, the attitudes of the judiciary, and witnesses committing perjury. For example, a 20-year-old South Korean student was acquitted of a drug trafficking charge in 2017 after a police officer admitted that he had lied in court.

“I’ve heard clients say that they’ve been framed. There are overzealous investigators who may want to ‘improve’ the evidence. There are professional witnesses who know how to give evidence,” says Amer Hamzah.

There are also structural problems, says Abdul Rashid Ismail. Accused persons who aren’t able to afford their own lawyers have to settle for state-appointed ones, which tends to boil down to sheer dumb luck: one could be assigned a veteran criminal defence lawyer, or a relative rookie with limited experience with capital cases. “You never know what type of lawyer you might get. It’s a lottery.”

Moreover, Rashid says that assigned counsel only gets paid RM6,000 per case, and so their resources are very limited. “Let’s say they want to challenge the expert called by the prosecution, but they don’t have the money to do it. Experts are expensive, and they’re not always readily available.”

“As long as there is human involvement in the investigation and trial process, there will be error. We can try to minimise the errors, but that’s the best we can do,” says Amer.

The current law and anticipated changes

For now, Mainthan and other inmates on death row have been afforded a temporary reprieve.

Whatever form the change in law ultimately takes, pending the tabling of a Bill in Parliament, the new Pakatan Harapan government has imposed an immediate moratorium on all executions.

This is significant in itself, for Malaysia has continued to use the death penalty in recent decades. More than 400 convicted persons have reportedly been hanged since 1960, and at least four were hanged in 2017 alone. Currently, there are more than 1,200 prisoners on death row. Most are facing execution for drug trafficking, followed by murder and firearms offences.

Currently, the death penalty applies to more than 30 offences—of which a third of them carry a mandatory death sentence. A mandatory death sentence used to apply for drug trafficking offences. But in 2017, an amendment to the Dangerous Drugs Act 1952 was passed in Parliament, which replaced it with a discretionary death sentence: judges would be bound to apply the death penalty unless limited conditions were satisfied.

With the most recent announcement that the government would move to abolish the mandatory death sentence as it applies to 11 offences, judges may have more room to use their discretion to take into account the specifics of the crime and the individual circumstances of the offender, in deciding on the appropriate sentence.

However, Abdul Rashid Ismail cautions, “At the end of the day, even under a discretionary regime, the arbitrariness will continue. Different judges will have different interpretations of certain aspects of the law, fact and crime. Judges are human beings, like us they are shaped by their own life experiences and prejudices. That’s why we need to abolish the death penalty in total.”

Meanwhile, throughout the moratorium, the Pardons Board continues to evaluate the appeals of clemency before them. In his meeting with the families of death row inmates in January, Liew said, “In drug trafficking cases where the convicted has been in jail for more than 30 years, maybe the Pardons Board can reconsider and release them or shorten their prison sentence. For heinous crimes like murder, we will have to review on a case-by-case basis. Maybe the perpetrators will have to serve a life sentence, without parole.”

According to Rashid, the Pardons Board—currently the final lifeline available to death row inmates—is not an adequate solution. “It doesn’t resolve the problem we have in a legal system that carries the death penalty because there’s such a lack of transparency in the procedure. We don’t know how it works, and its decision can’t be challenged in court.”

Some of those who support the death penalty have decried what they see as the government putting the rights of convicts over the rights of victims. Rashid says, “When we call for the abolition of the death penalty, we are not saying that we are not going to punish the wrongdoer. Of course we want the wrongdoer to be punished: that is always the position. The victim’s family will still get justice by sending the wrongdoer to prison, possibly for life. It is not for the state to take the lives of its own citizens.”

CORRECTION: The Criminal Procedure Code in Taiwan was revised in 2015 instead of 2016. A public opinion survey was also mistakenly attributed to the Attorney-General’s Chambers rather than the Death Penalty Project. Apologies for the errors—they’ve been corrected in the story.