By Kiran Jacob | The Edge Malaysia

There are similarities between the United Nations Guiding Principles (UNGPs) and the proposed NAPBHR in Malaysia. However, the NAPBHR will need to be context-specific and address the country’s actual and potential human rights violations, says Dr Punitha Silivarajoo, Deputy Director General (Policy and Development) of the Legal Affairs Division in the Prime Minister’s Department.

The UNGPs are a set of guidelines for states and businesses to prevent, address, and remedy any adverse impacts on human rights. Meanwhile, the NAPBHR is a document that articulates priorities and actions that the government should adopt to support the implementation of international, regional, or national obligations and commitments with regard to business and human rights.

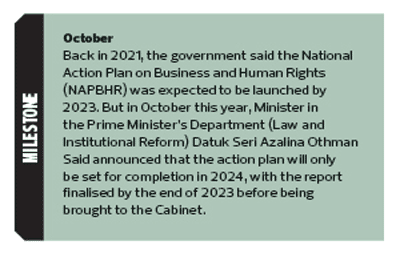

The NAPBHR is set to be completed by 2024, with a steering committee to be chaired by Datuk Seri Azalina Othman Said, Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department (Law and Institutional Reform). It will be supported by the Legal Affairs Division alongside the Human Rights Commission of Malaysia and the United Nations Development Programme.

The NAPBHR was to have been released earlier, but unavoidable events such as the COVID-19 pandemic caused a delay, says Punitha. It affected the entire process, including the appointment of experts to undertake the national baseline assessment (NBA).

“The NAPBHR will need to reflect the state’s duties to protect the people against adverse business-related human rights impacts. Furthermore, it needs to promote human rights due diligence to businesses, which include large corporates and small and medium enterprises, and measures to allow for access to remedy if there are any violations,” says Punitha.

She says the NBA report outlines the current state of human rights in Malaysia. Once the government receives the NBA report, engagement sessions with representatives from the ministry will be conducted to confirm the information and findings in the report.

“This matter will take time, since the in-depth study and information review process need to be carried out carefully, considering all relevant aspects.”

Punitha says the NAPBHR will be used to encourage companies to take note of the gaps highlighted in the action plan. Subsequently, necessary action will need to be taken to overcome them. It is to be noted that the NAPBHR will not be legislative and will instead serve as a guideline to the government.

“This is because Malaysia’s legislation is complete and sufficient to overcome many human rights issues. Strict enforcement is needed and therefore the NAPBHR will have to address these enforcement issues,” says Punitha.

“Despite there being many prior frameworks of policies and laws to deter forced labour and other human rights violations, ultimately, the relevant stakeholders will need to decide what’s the benefit from a business sense to prevent forced labour and other human rights incidences.”

Make due diligence mandatory

Rapid economic growth has led to significant reductions in poverty. However, it has also given rise to human rights issues.

To overcome these issues, businesses need to ensure the protection of workers’ rights, humane working hours and safe working conditions along with fair pay in factories while promoting women’s rights and economic empowerment. Businesses will also have to conduct due diligence on human rights, says Edmund Bon, a lead consultant for the NBA report and the Head of Chambers (Civil) at AmerBON, Advocates.

Due diligence involves a 6-step process, rendering it more than just an audit, says Bon. This is detailed in the book, Business and Human Rights in Southeast Asia: A Practitioner’s Guidekit for SMEs on Human Rights Compliance regarding the Environment and Labour, of which Bon is a contributing author.

The first step is to embed responsible business into policies and management systems. The second step would be to identify and assess adverse impacts on operations, supply chains, and business relationships. The next step is to cease, prevent, or mitigate adverse impacts and thereafter, track implementation and results. After that is to communicate how the impacts are addressed. The final step is to provide for compensation and cooperate in remediation.

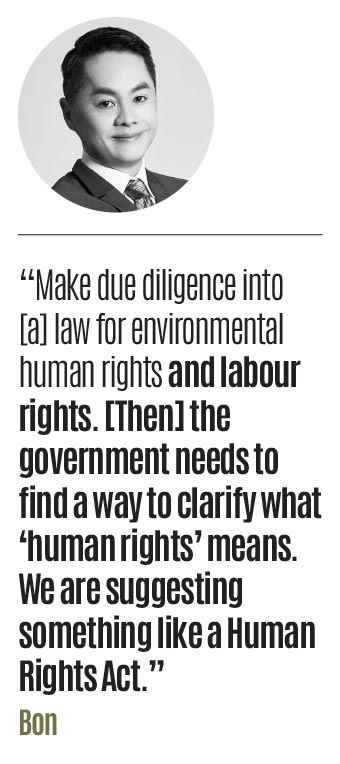

Bon stresses that mandatory due diligence for labour, governance, and the environment must be implemented.

“When we say mandatory, we’re saying you need to make it [a] law. Make due diligence into [a] law for environmental human rights and labour rights. [Then] the government needs to find a way to clarify what ‘human rights’ means. We are suggesting something like a Human Rights Act,” says Bon.

“[This is because] human rights are misunderstood. We need legislation to explain what [are] human rights. The Federal Constitution doesn’t use the term ‘human rights’. It just uses ‘fundamental liberties’.”

Mandatory due diligence on human rights should be done using a phase-by-phase approach, he adds, with a suitable time frame for companies to prepare.

Of course, the NAPBHR should not be the only solution, asserts Bon. Instead, companies should be gearing themselves to work on the different initiatives to protect human rights. He also says that since law, justice, and human rights are big issues in the country, there should be a full-fledged ministry on human rights and justice.

“Without the NAPBHR, you can start now. [For instance], through ESG (environmental, social and governance) initiatives, Bursa’s mandatory reporting sustainability indicators, as well as its enhanced framework,” Bon suggests. “If [companies] start now, then they will already be ready and may even far surpass [the NAPBHR].”

This article first appeared in The Edge Malaysia Weekly on December 25, 2023 – January 7, 2024.